This post is co-authored with Ernesto Costa, Agritask’s board member and BlueOrchard’s Head of Private Equity Investments.

Climate change is defined by National Geographic as: “a long-term shift in global or regional climate patterns. It typically is used in the context of the rise in global temperatures from the mid-20th century to the present day.” Everywhere we look across the world, traditional weather patterns are being upended. In some regions, winters are becoming warmer and longer, while in others, summers are becoming more temperate and shorter. These climatic changes are creating droughts, hurricanes, floods, mega-fires, and rising sea levels.

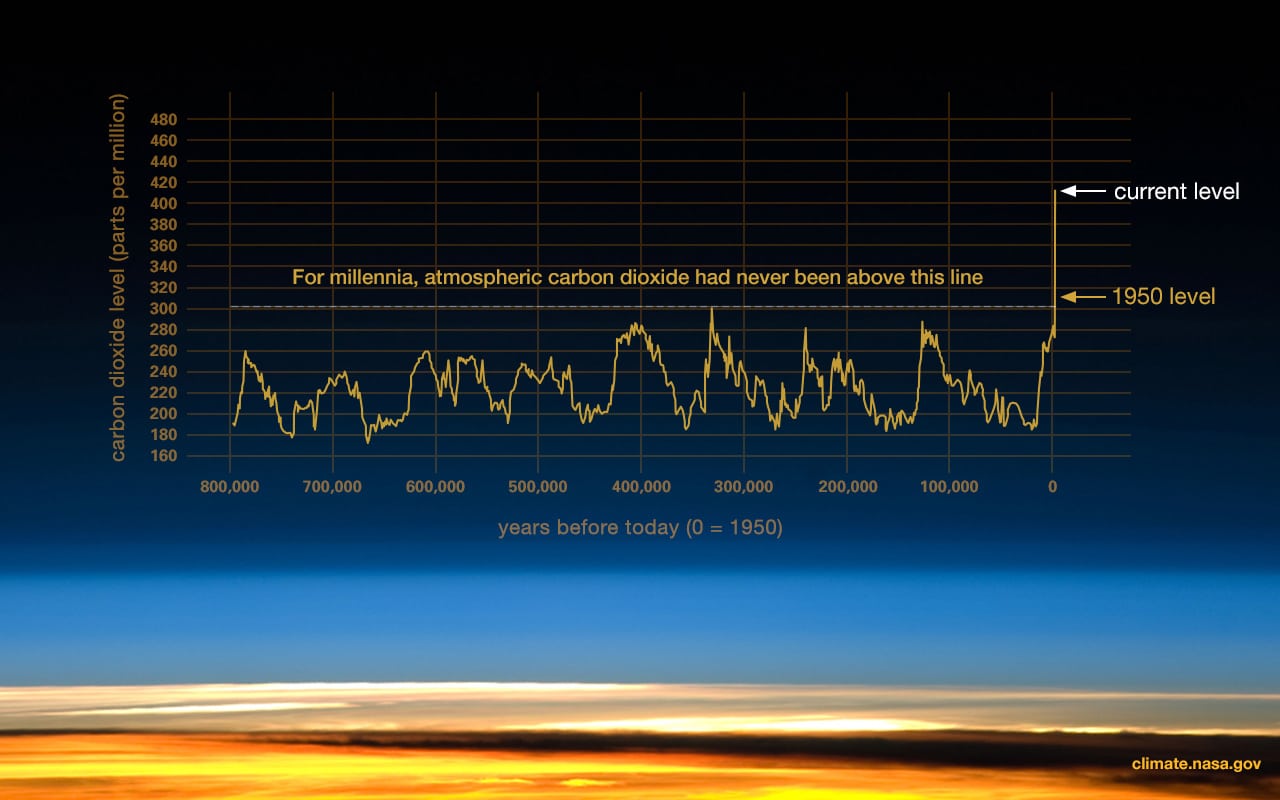

Climate change is real; it’s not just a buzzword. According to NASA:

- Carbon dioxide emissions have caused the Earth’s average temperature to rise by 1.18 degrees Celsius (2.12 degrees Fahrenheit) since the end of the 19th century.

Source: NASA

- Since 1969, the oceans’ temperature has increased by more than 0.33 degrees Celsius (0.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

- Greenland’s ice sheets lost 279 billion tons of mass each year from 1993 to 2019, while Antarctica lost 148 billion tons each year.

- Sea levels rose by approximately 20 centimeters (8 inches) in the 20th century.

Agriculture relies on a stable climate

Throughout the history of humankind, local climate has dictated agricultural production – the type of crops and livestock raised-. Global climate change is disturbing the delicate local agricultural ecosystem in many regions, and especially in developing countries.

For example, increased global temperatures are negatively impacting the growth of beef cattle. While considered less susceptible to heat stress than dairy cattle due to their lower metabolic rate and body heat production, beef cattle compensate for higher body temperature by panting, sweating, and urinating more frequently. Also, when their body temperature rises, beef cattle modify their behavior: they reduce their physical activity, drink more water, and eat less. The sum effect of these actions is a lower birth rate and reduced fertility levels for both male and female beef cattle at a time when global demand for beef is rapidly growing.

The significance of these changes is monumental across multiple dimensions. Specifically, the Ricardian method enables us to learn about the long-term effects of climate change on the agricultural industry. Studies predict a substantial decrease in farmers’ revenues in developing countries as a result of climate change, which can be significant if no adaptation measures are taken.

Developing countries are more susceptible

The world’s most vulnerable populations — the majority of whom live in developing countries — will bear the brunt of the damage of climate change. Most of the households in these regions are dependent on agricultural production as their primary source of income. Smallholder farms (which make up more than 90% of the world’s farms) are mostly rainfed, and therefore particularly vulnerable to climate change. Poor infrastructure, deficient farming techniques, lack of access to finance, quality inputs and markets, only aggravate the situation.

Rising temperatures will cause crop yields to decline, resulting in food security issues and declining exports for developing countries.

According to McKinsey, changing weather patterns in Africa are destabilizing yields for both livestock and crops across the continent. Even more disturbing is their claim that this is only the beginning; rising temperatures will increase the severity of extreme events and continue to shift what have already become highly volatile rainfall patterns. In Kenya, climate change is transforming regional economics as the country experiences a severe geographical shift in the areas that receive rainfall.

Climate resilience in practice

A specific example of a successful climate resilience-building project is the one conducted in Vanuatu, one of the world’s most vulnerable countries to climate change and disaster risks, including tropical cyclones, tsunamis, droughts, coastal flooding, and sea-level rise. This project aimed at increasing the resilience of communities, particularly women, young people, boys, and girls, to shocks, stresses, and uncertainty caused by climate change.

The project helped communities undertake adaptation actions like replanting hybrid plant cuttings from demonstration plots, using solar dryers to preserve their food ahead of the cyclone season, reusing water, and cooking scraps to increase the nutrient levels of their soils. It also promoted continued engagement with their local government departments on climate adaptation.

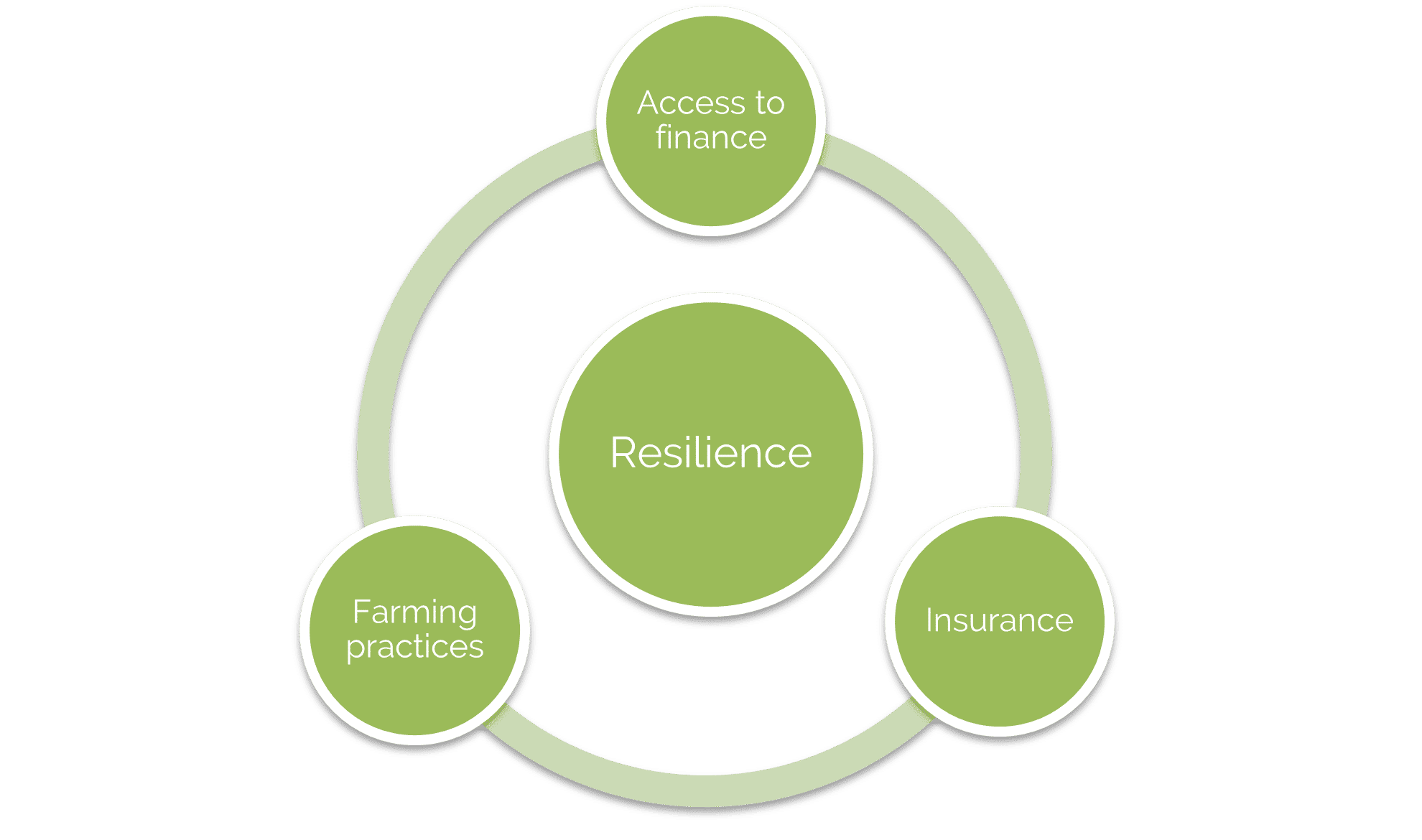

The best way to support developing countries’ struggle with climate change is to help them build climate resilience. For the food and agricultural sectors, this is achieved through two pillars: (1) mitigating risks through better practices and (2) transferring risks to stakeholders better positioned to absorb them.

Mitigating risks through better practices involves the accelerated adoption of innovative agronomic practices enabling vulnerable farmers to reduce the potential damage from issues caused by climate change. The use of drought-resistant seeds, for example, could alleviate the impact of changing rainfall patterns. The introduction of modern irrigation methods, pest monitoring and eradication practices are additional examples of innovative adaptative practices.

Transferring risks to 3rd party stakeholders. Transfering immitigable risks from farmers to institutions better positioned to absorb them – like governments, multilateral agencies, insurers and reinsurers – shifts the financial burden caused by climate change away from individual farmers incapable of sustaining it. De-risking the agricultural production facilitates access to financing, fueling further investments to enhance farming operations, which in turn further reduces risks.

Both pillars create a reinforcing loop or virtuous circle. Intervening in both of them simultaneously, for example, investing in better seeds and irrigation and buying insurance cover, only compounds their positive effect in building resilience to climate change.

However, to put the wheel in motion, i.e. improve farming practices and create risk transfer capacity, the agriculture ecosystem faces one major challenge: data, and more specifically, agronomic data. It is about the lack of data and, most importantly, the ability to consolidate data from varied sources and interpret them at the very local level.

Agronomic data are key to build climate resilience programs. Without data, how can the farmers improve their operations, insurers and lenders assess and price the risks, and stakeholders understand the cost benefits of any program?

Many ag-tech solutions providers are trying to tackle the issue. Agritask has developed a scalable data-driven agronomic platform that allows farmers and their stakeholders to enhance productivity, use inputs more effectively, and manage agricultural risks. The platform already supports 230,000 farmers across the globe in building climate resilience and is used by international insurers, reinsurers and regional programs. We have witnessed how multiple stakeholders’ collective effort makes a difference in responding to this unparalleled climate change threat.

Conclusion

Climate change is continuing to disrupt the world’s long-term weather patterns. The agricultural industry is especially susceptible to climate change because of its inherent dependence on traditional weather patterns to sustain productivity. This susceptibility is more acute among farmers in the developing world who are especially reliant on natural resources and have less access to products, markets, and services, including insurance, that can mitigate climate change risks.

We believe that providing data to all stakeholders from one platform, with a holistic view, is a major contribution to climate adaptation in developing countries because it empowers farmers to improve their agricultural operations and enables access to insurance and financing.

The issues covered in this article are just the tip of the iceberg. Issues such as pests, food security, early blooming, and regional-specific implications will be the subject of future articles.